Ai Weiwei’s collaboration with Herzog & de Meuron’s Hansel and Gretel at the Park Ave Armory (June 7–August 6, 2017) raises unintended questions about surveillance, it’s limits, applications and interrelation with consumerism. Justifiably, we anticipate the merger of an infamous political dissident and big-budget cultural complex architects to forge an insight into one of Western society’s most prescient questions, and be able to inhabit that insight and see it from the perspective of dissident on whom surveillance has been exercised. But instead we encounter an obtuse approach to the predictable power structures of observation laid in a path to techno-aesthetics that feel as dated as the Patriot Act I. But there’s more. (If only it were intentional.)

The Park Ave Armory, 2017

The two part installation buttresses an archimedean point–a door–at which the visitor occupies the role of the prison guard in Bentham’s panopticon model, on a staircase landing, a peeping-hole. I’m starting at the end of the journey, rather than the entrance. Performing the critique we expect from the designers, we look back at the prior point of the installation in the Wade Thomson Drill hall, see our past selves in the innocent and unaware visitors, experiencing the previous stage of the journey. We had entered the dark room with hovering drones and projections of image-capture and one part control-station part research-space. We had walked from Lexington Avenue, down a dim, black velvet corridor, the exit of which into the Drill hall felt expansive: the unlit void located gray rectangles lain over the subtle arc of the floor. We had looked. Seen. Moved around. Exited. Re-entering on Park Ave, we had paused at the camera, then journey up the staircase and from the peeping hole, the those places of contemplation and play, look to float in an ether. Platforms of light with shadow dancers. I saw people sort of dancing, walking, pausing, contemplation. Each area within this nowhere space varied by intensity of brightness; some were entirely dark. Red rectangles within these platforms of light freeze images of your movement. This became a choreography of surveillance, an exchange of image for movement, interacting with your own captured, flattened representation.

There’s a level of theatricality in the installation at the Park Ave. Amory. Like a Grotowski play in which even the audience has been removed, visitors move around dimly lit rectangles, gazing at their own image projection that is being captured and encapsulated with an enigmatic red box as drones hover above creating a refreshing current of cool air amidst the otherwise stagnant darkness.

Dancers, 2017

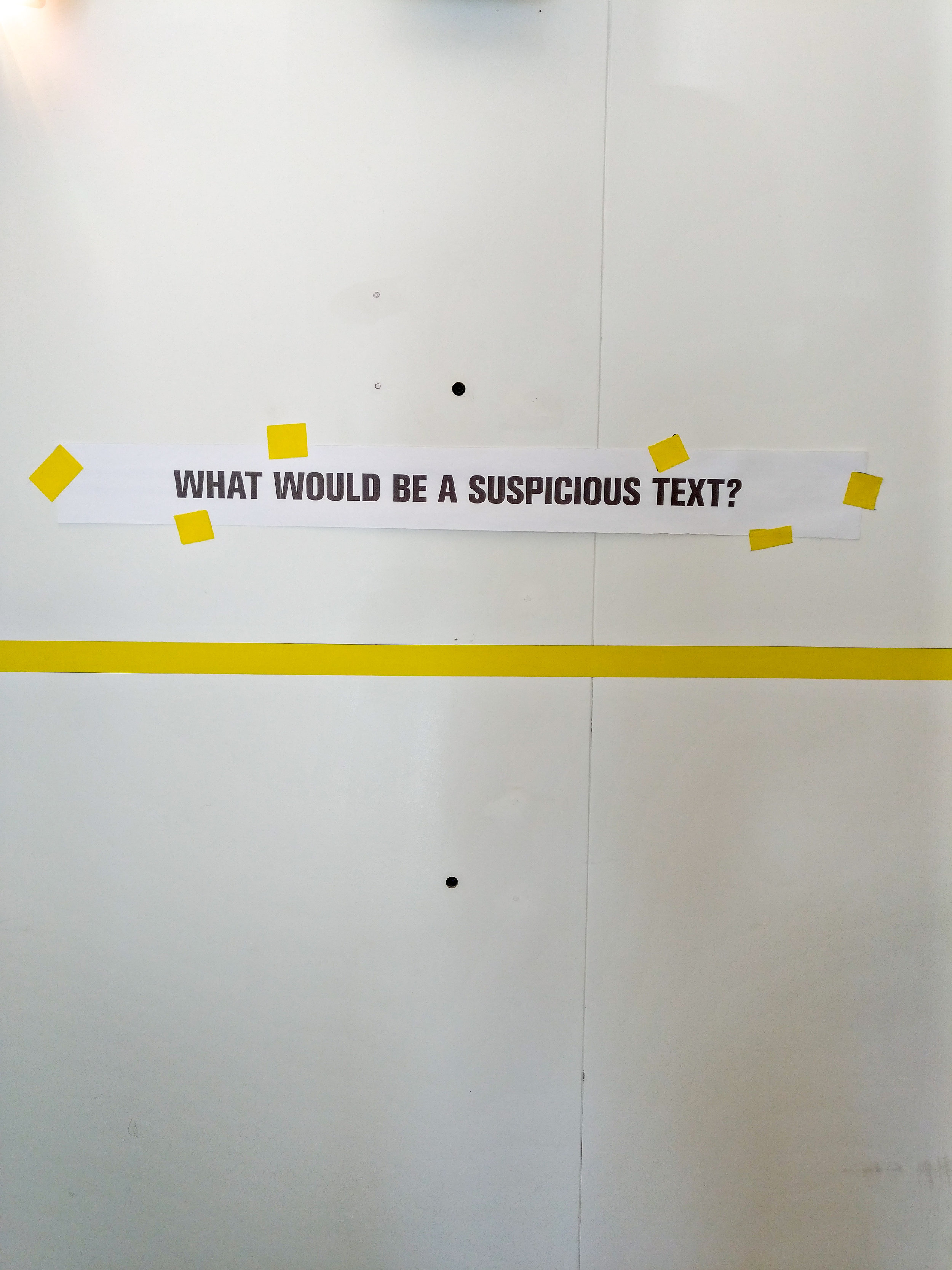

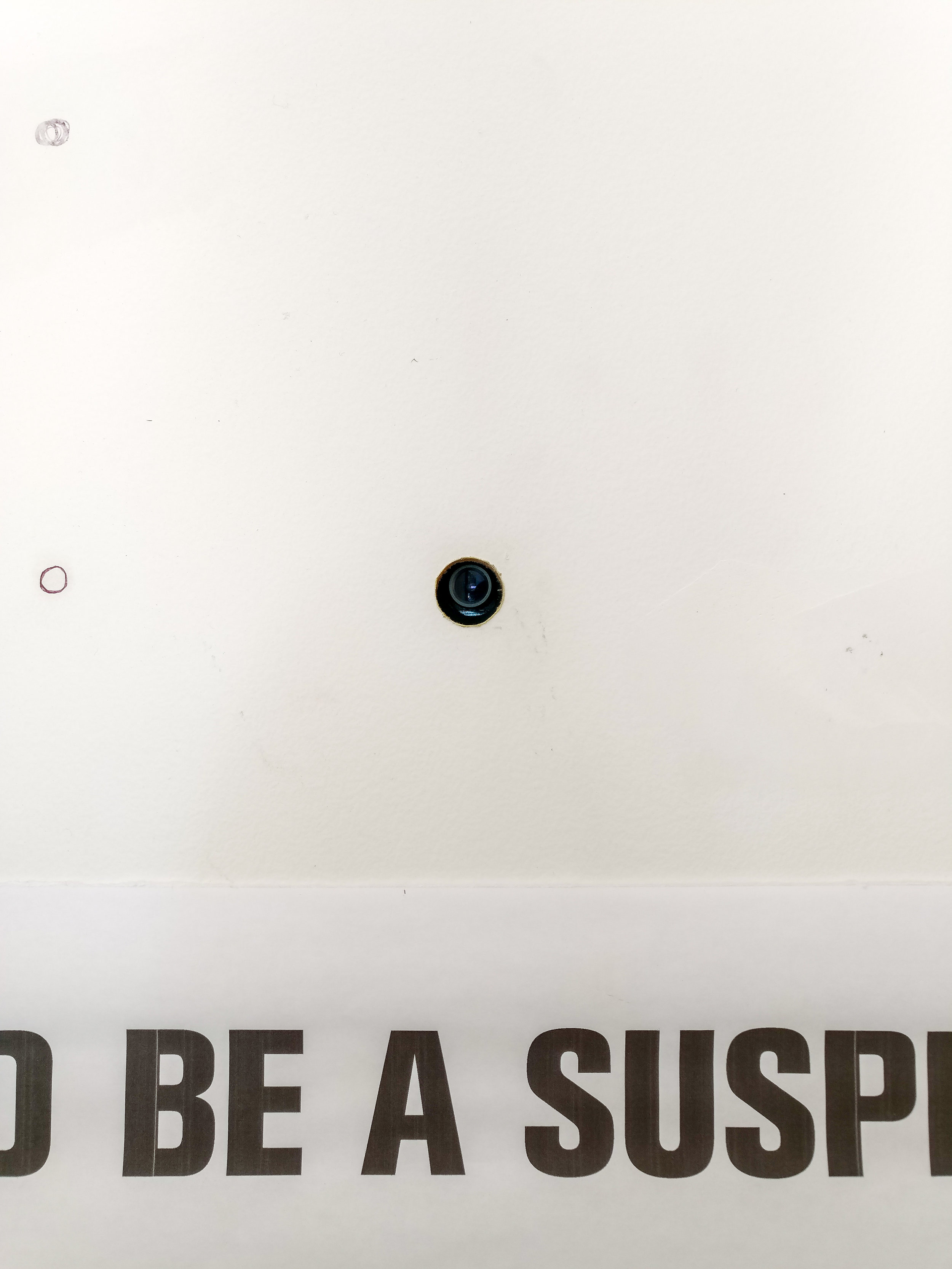

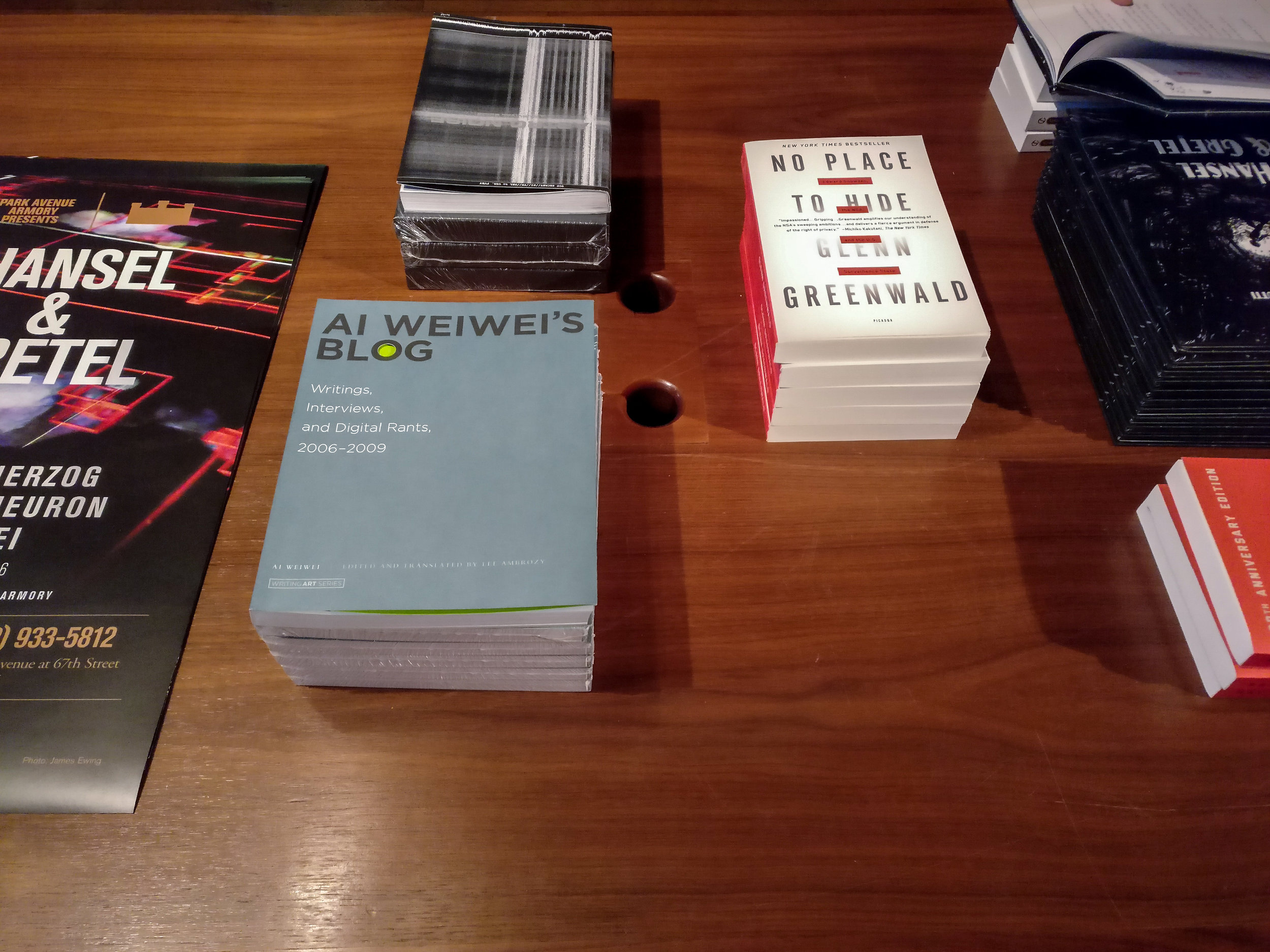

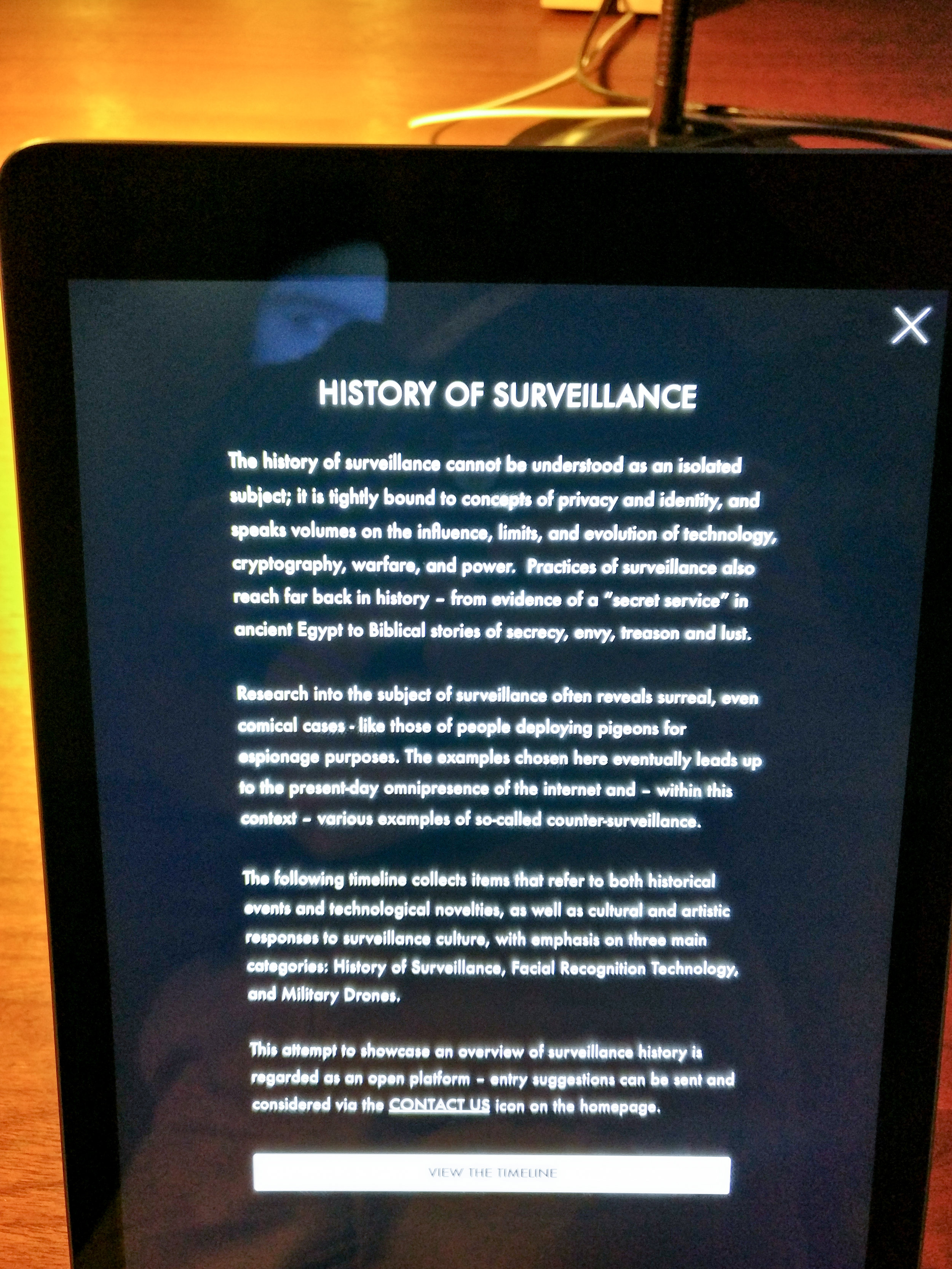

But on the floor of the drill hall, the buzzing of drones swaying on cables like an invisible chandelier, stirring up a cooling summer breeze vertiginously against the gaze to the floor onto which one’s image captured from above is projected, seems partial, incomplete, wanting. There was the persistent sense that this wasn’t all there was supposed to be, and, in fact one was under surveillance. Upon entering, a text printed in large, bold typeface was pasted on the wall, bracketed by a partially-hidden but obviously working camera above and below the paper set up a, “Ok, when are you going to show me enjoying this moment that I’ve almost forgot is about surveillance.” Exit through the blue light in the corner, walk around the building. Re-enter on Park Ave, have your ticket scanned, pause in front of a red light as instructed and see your face in nightvision displayed on the wall. The hallway diverts right and left. To the right, sure enough, you see those cameras of the entrance on Lexington, streaming on a wall. Boring. A series of tables with iPad invites you to find your face, i.e. the accuracy of facial recognition, and look over a website showing (one) history of surveillance. Ok, but why am I here? I mean, I can see the website anywhere, right? (Why pay $17 to look at an iPad webpage?). Conjoining these two spaces is a flight of stairs up to the peeping hole. Next to the hole is a symbol of a eye printed on 8.5 x 11” paper, calling those below to come, peer. Please.

When you’re interacting with the drones, you know you’re being watched–that’s the point–but you don’t know you’re being watched from the staircase. And as you enter at Lexington Avenue, and read the blunt text that’s been Flex Taped® on, you see the small camera’s recording you. When you re-enter on Park Avenue, you’re asked to stop at the camera.

From the peep hole, the supposed end of the route of surveillance. The title alludes to the trail of breadcrumbs left by the children as they were led into the woods to die, the trail which leads them back home. In the digital world, particularly online but increasingly in the physical world, we leave sorts of breadcrumbs that can be traced back to our individual, our person, our identity. The second section is demonstrates the basic facial recognition technology by capturing visitors’ upon entrance, pushing their image onto large wall monitors and inviting one to search their own face through the aid of an iPad. Your face, like a fingerprint, can be a breadcrumb.

The immediate recollection of Laura Poitras’s installation in Astro Noise at the Whitney Museum in which the visitors are invited to lay down and gaze at ceiling projection of stars and later, upon exiting, have the curtain pulled off their head to reveal, ta-da! You were being surveilled! Thematically, Poitras’s surveillance work, specifically the mobile phone scraping piece in the same show, recalled Trevor Paglen’s show at Metro pictures in 2015, in which he presented Autonomy Cube (2015), which is a wi-fi hotspot that sends all traffic through Tor browser relays. The gesture offers a semi-anonymous browsing experience, lacking only a VPN for further anonymity, but really smartly conveys the existence of Tor to the fine art world crowd, as Poitras’s mobile scraper displayed the technology of capturing telecommunications data, as Weiwei, Herzog and de Meuron demonstrated the surveillance application in the consumer grade drones. But again, surveillance technologies within the safe space of art institutions are distinct from how those same technologies are implemented by a government on a campaign against “terror” and with the exception of a few art world players like Ai Weiwei, Poitras, and Paglen, the governmental surveillance largely omits members of our socioeconomic class, occasionally deviating along racial and religious lines. And its in this elision and inconsistency that the facade of surveillance comes to light. The technology and infrastructure may reach all, but is applied directly to few. A simple test is to search how to make a ____________ on Google. Go ahead, do it. You won’t be folded into the NSA nor FBI nor CIA database to have a sting operation rendered. You won’t be stopped at an airport. Practically speaking, it’s this inconsistency through which we as a majority continue to allow the Patriot Act’s sunset to extend and parts of the expired act to be reinstated USA Freedom Act. Most don’t feel the direct consequences of being surveilled because the demonstration of power has a preconceived recipient in mind. As a predominantly white, middle to upper class crowd, the art world are more like voyeurs of surveillance than subjects of its protocol.

Weiwei, Herzog & de Meuron aren’t trying to trick you indefinitely. They want to give you the experience of switching roles, being the children who ultimately shoves the old hag in the oven and escape from her dinner clutches. They seem bound by the unspoken ethical chains that dictate in order to critique surveillance one can’t recapitulate its hierarchy upon the artworld visitors to the show. Here, the question of how to persuade us of the existence of tools of surveillance is answered by a strategy of deference, role switching. But there’s a lack of control in this shape shifting when one realizes surveillance with a capital S doesn’t apply in the world of art as it does outside the rarified walls of the museum. In fact, the art world–its patrons, artifacts–have been using tools of surveillance not only since the beginning of photography when subjects we aligned with the exceptionality of the artistic class—the proprietors of art, the creators, portraits and art reproductions—which weren’t surveilled in the sense of be disempowered or controlled by image conveyance but empowered by it. The art world has willingly adapted CCTV systems in museums, galleries and fairs.

Surveillance tools in the museums are not constructing the criminal from the social body of members of the artworld, as in the criminal is constructed in the social body more widely, through the aid of cameras that offer “proof” to the person’s criminality. Surveillance is not a person in relation to a technology, but a relationship of power whose reach is extended through the confluence of lens glass and sensor and screen and imputed into a judicial system. And so here in the armory of Park Avenue, one of the wealthiest streets in North America, we can’t say that these cameras are subjugating us in the prisoners in the Panopticon. These are not peering for the minority who’s jumped the subway turnstyle, or shoplifted. These are not police body cams. No one is using the footage or purview to exorcise their domination over us; we, the good patrons of the artworld, self monitor and self regulate. We play all roles here. Sure, we’ll switch, but it’s weightless. And it is this tradition of near-horizontal power that informs the ethics of this space.

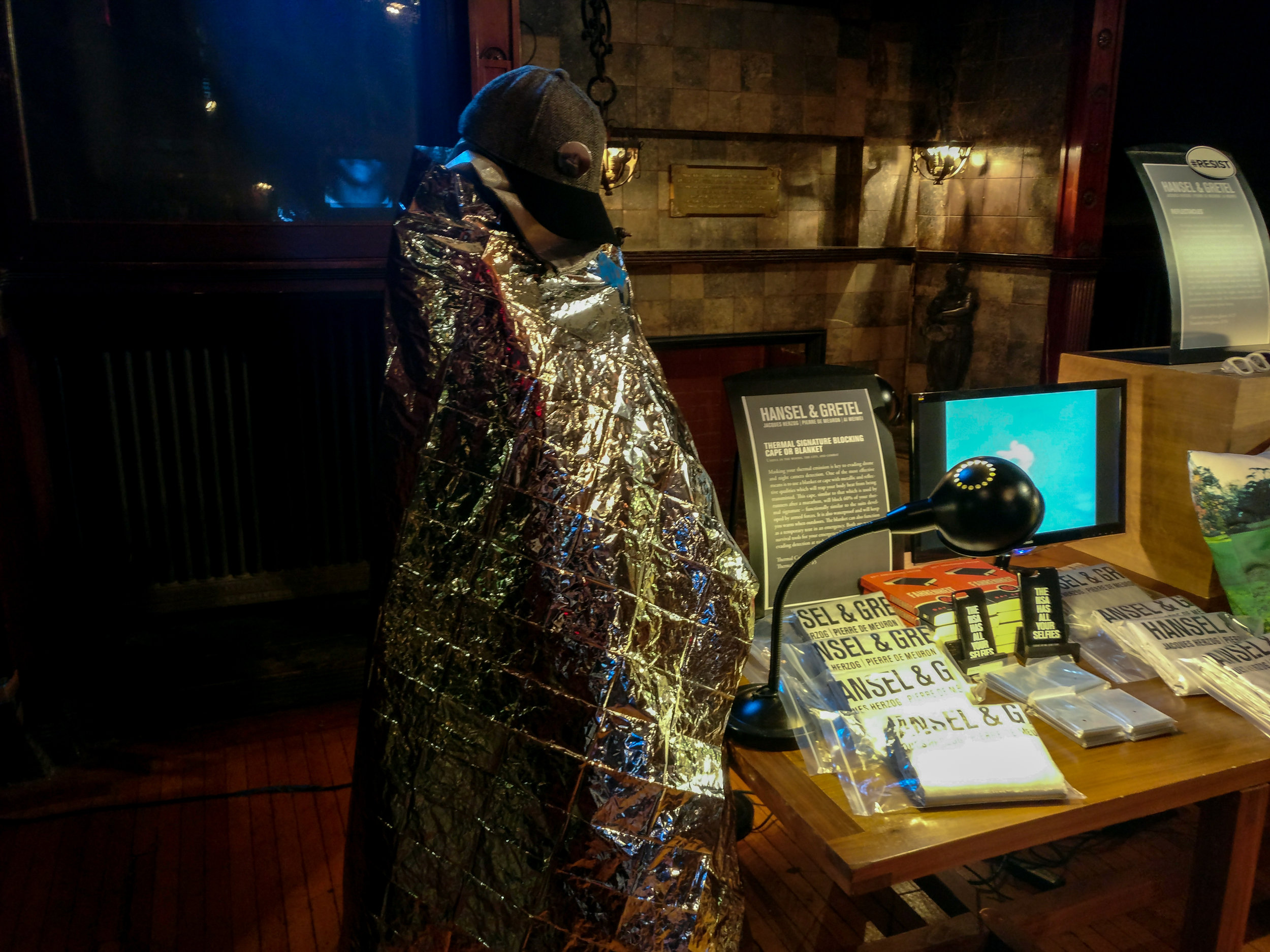

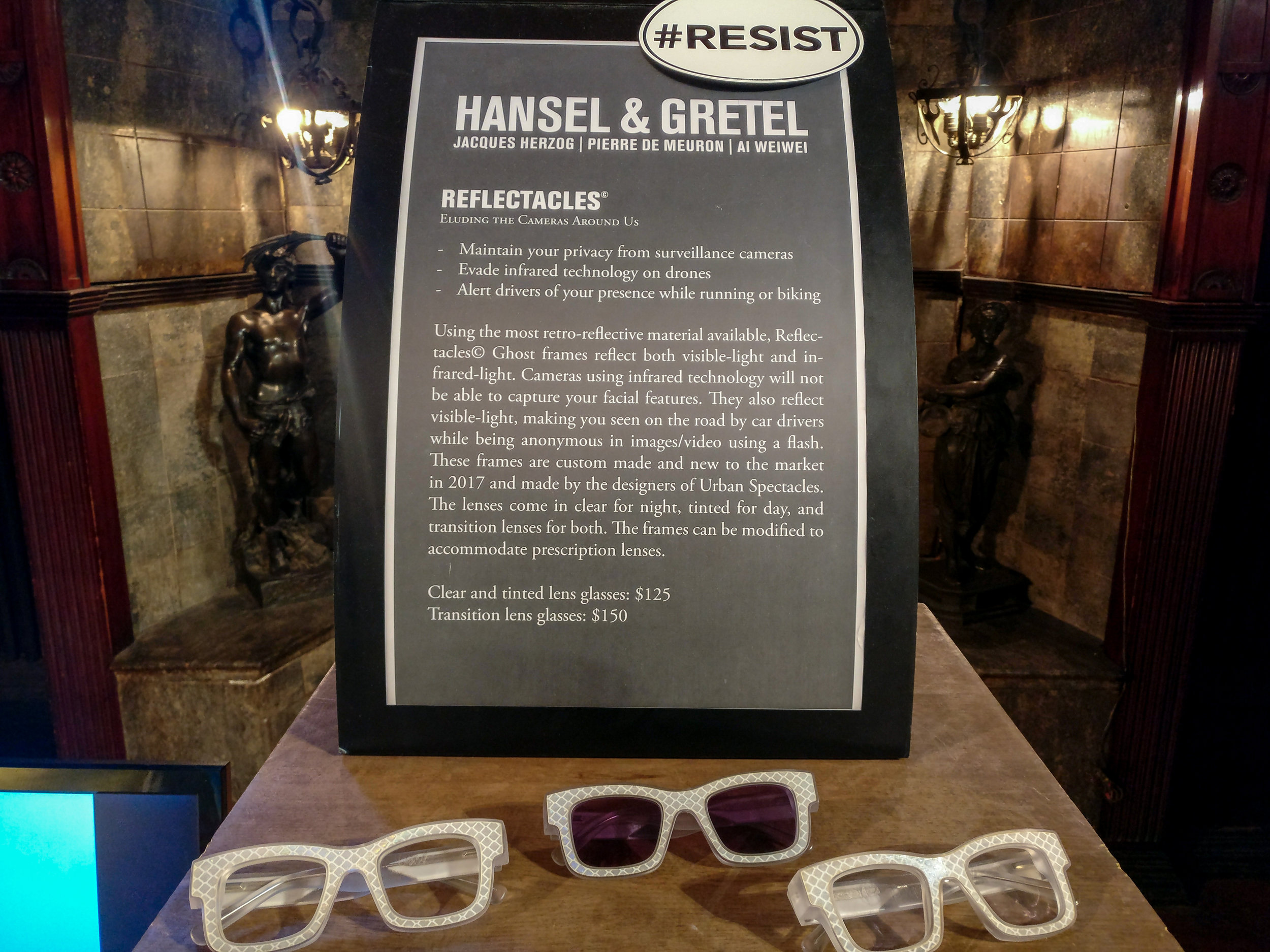

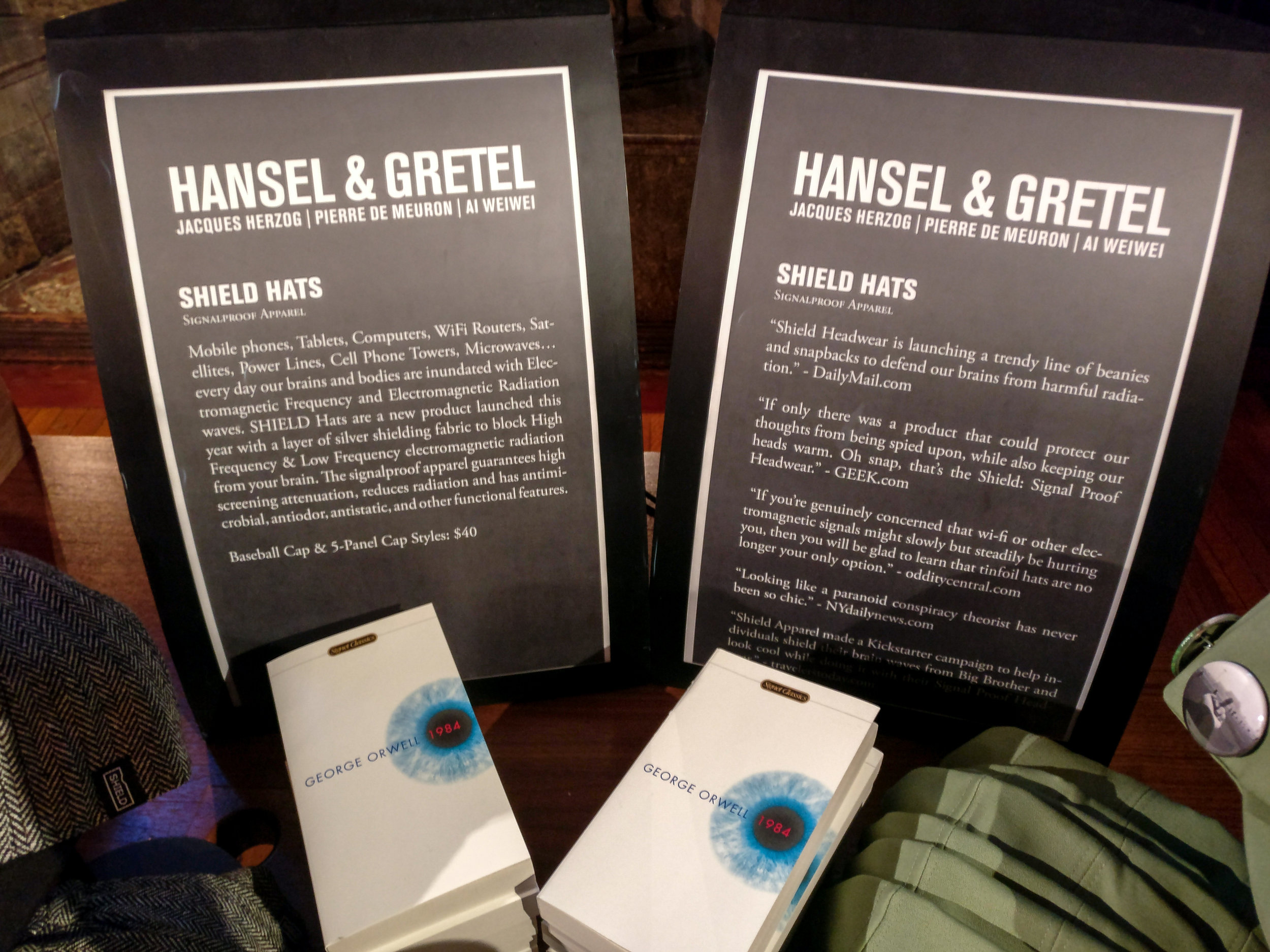

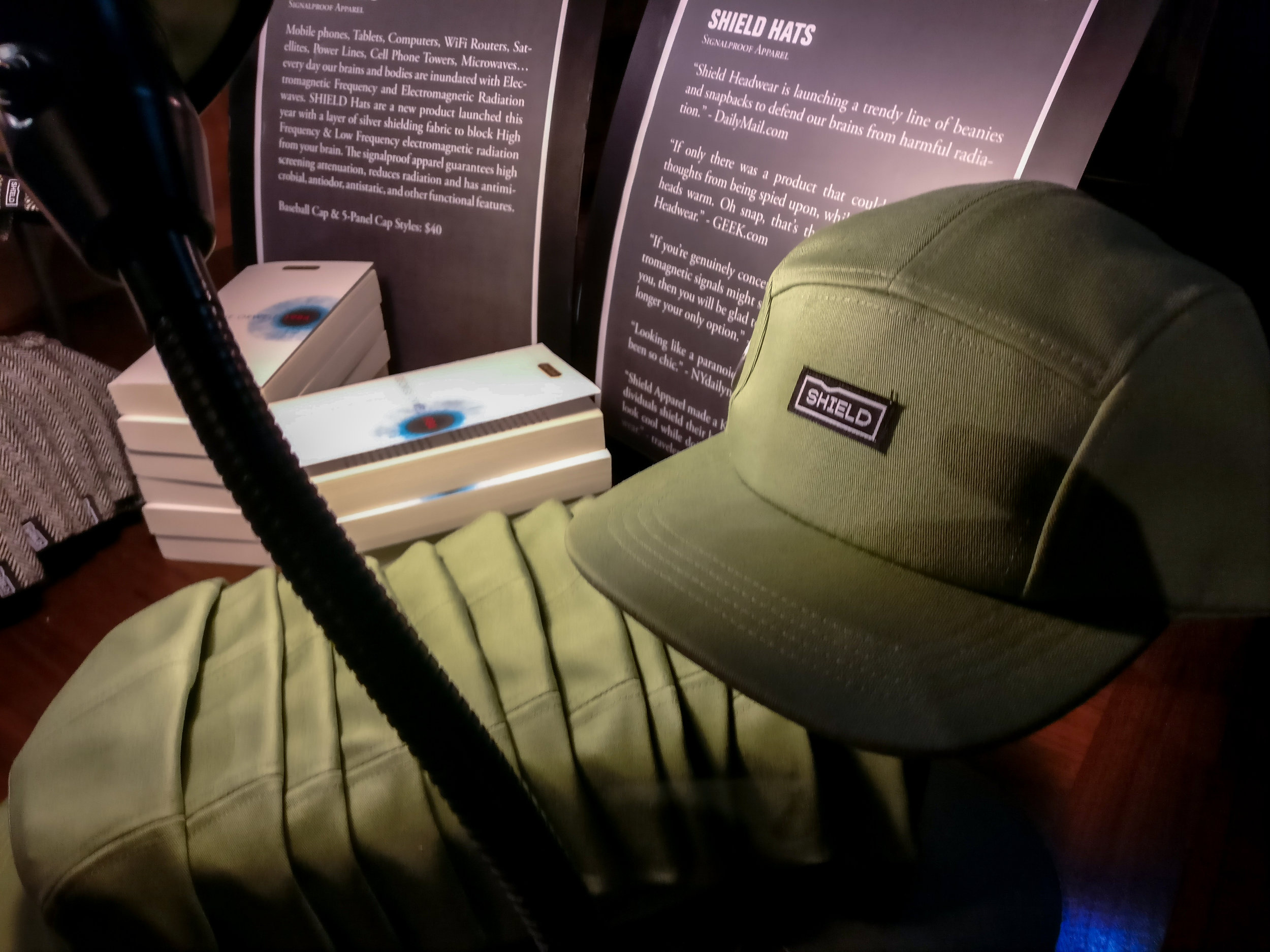

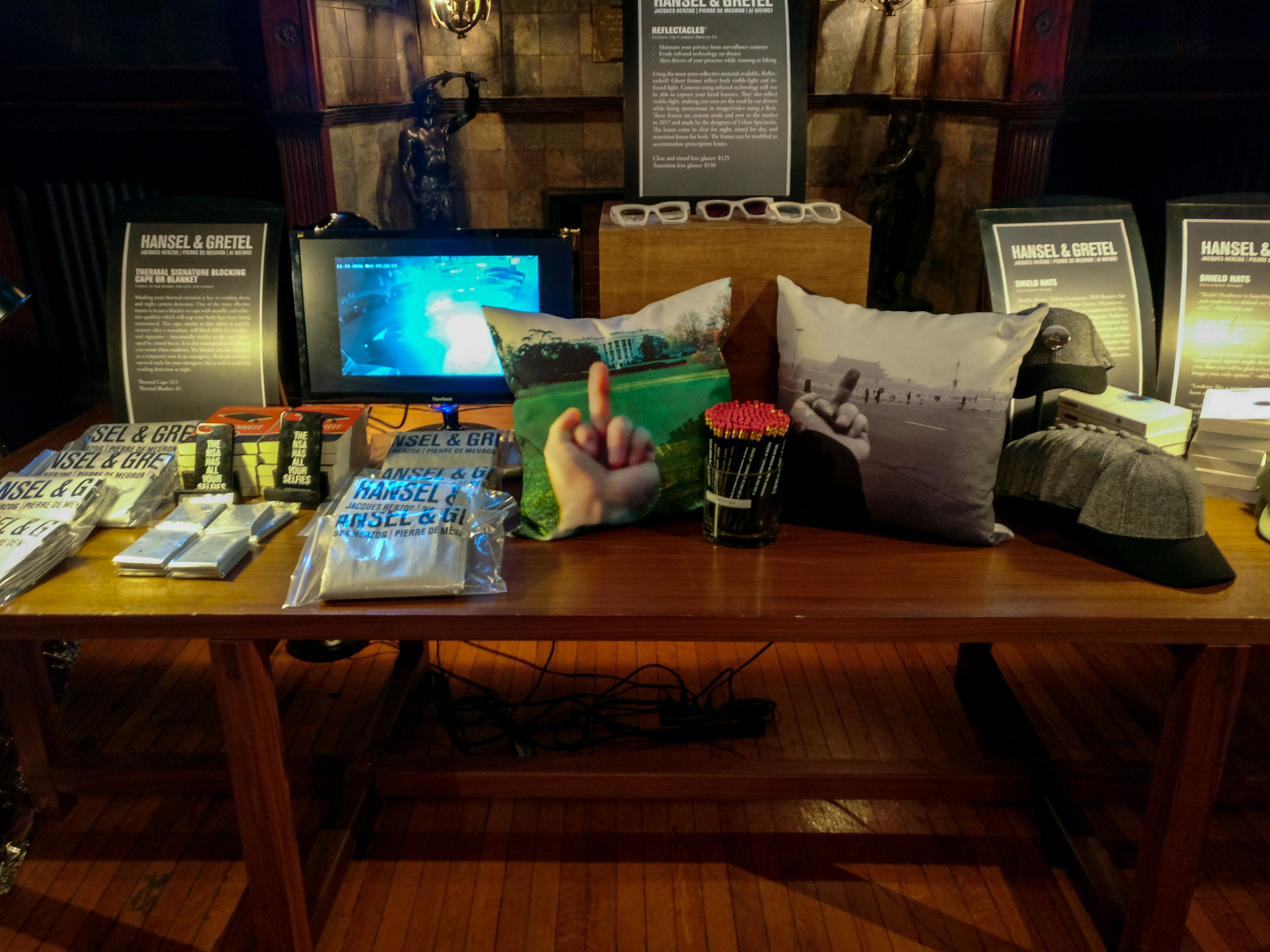

As a demonstration of the technologies that can be used for surveillance like drones with motion tracking, face recognition, and pinhole cameras, the trio of Weiwei, Herzog & de Meuron show us what they found at last year’s Black Friday sale. All of this is pretty tepid until you enter the gift shop. In fact, the gift shop really explodes what’s absent in this turgid critique of surveillance, which is not a demonstration of a technology, but how these socioscientific principals are weaving their way through a consumer society. The gift shop has the expected memorabilia of books and posters of the show, but the cell phone case, thermal signature blocking cape and blankets, glasses with reflective lenses that block face recognition, Faraday bags and RFID wallet to protect your financial data from being maliciously intercepted. There are shield hats that block all the electromagnetic frequencies that are bombarding us. Aluminum helmets, anyone? At first glance, all this seems to hint at a subtle acceptance of daily, integrated paranoia. But we should be more attentive to why a consumer product is a solution legal reality. Nothing is new, novel, nor interesting. In fact, it’s banal. It’s banal, literally. It’s banal to the extent that all the technologies that are exhibited have consumer-grade products that can foil them, all for sale, right there in the gift shop. What’s more banal than a technology that’s already reached a level of having mass consumer-level defense? Inadvertently, the gift shop is the most interesting aspect of the exhibition because it shows us the relationship between surveillance at consumerism.

Although unintended, this is the real conclusion to the exhibition journey. You’ve descended down the stairs from the peephole, you’ve checked out the iPads, you’ve seen your facial recognition, you’ve seen people entering on Lexington and like hungover, hungry Sunday morning you start rummaging through the remaining doors of the Armory, looking for something to justify your $17 entrance ticket. The gift shop. Holy shit.

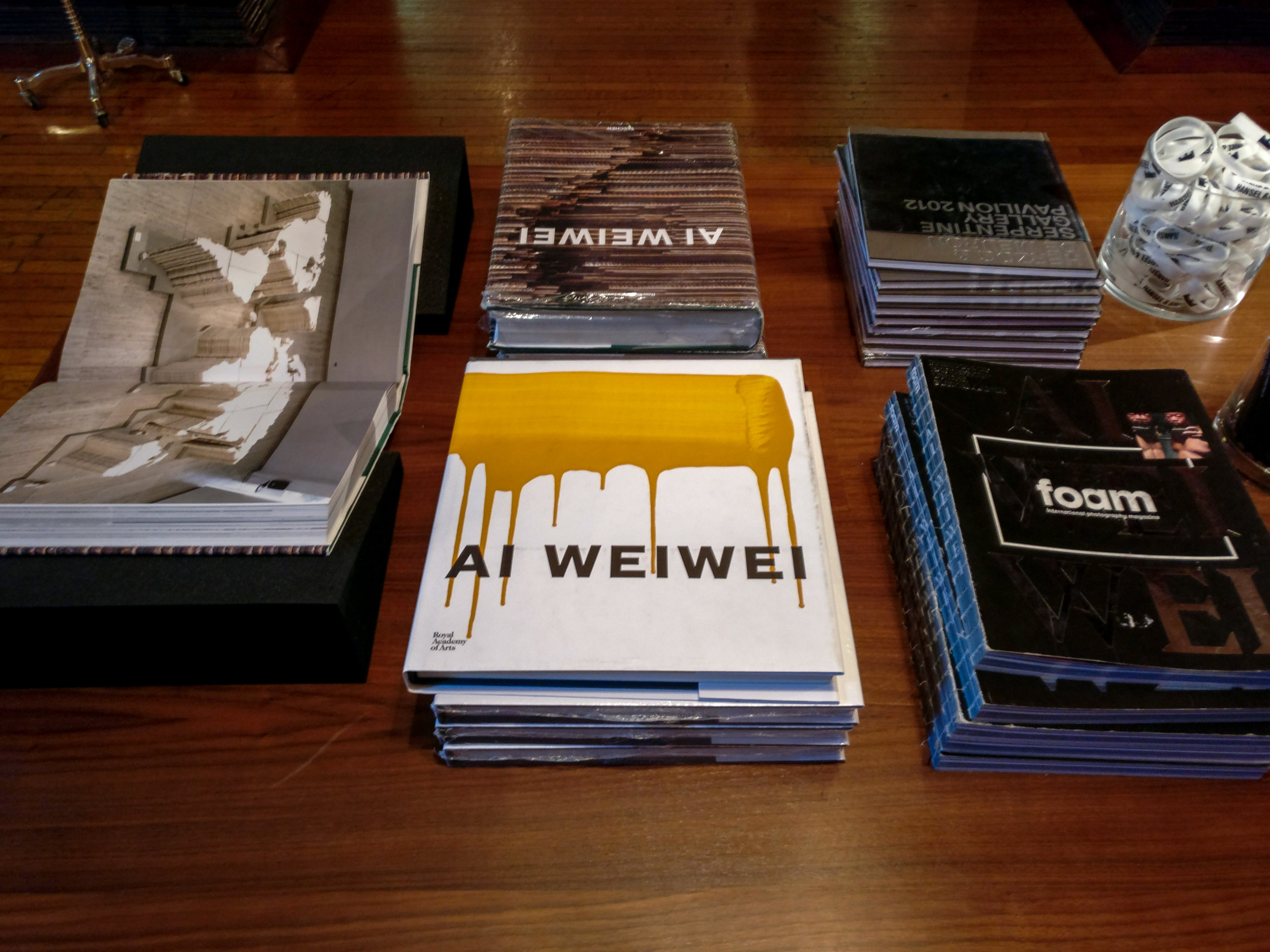

Ai Weiwei. (Is there on Hello Kitty-esque Ai Weiwei shirt? I get the monographs, sure, but the throw pillows? Seriously? Remember, this exhibition isn’t a critique of consumer society. It’s about drones. Wait. And architecture? The website’s good, check out the website. On Herzog & de Meuron’s site there’s a sort of promo video that aligns the project to closed circuit TV tradition by dividing the screen area into four separate feeds, which at once show the armory’s programming and decoration. It’s okay. ) In the wake of Edward Snowden messing up all the NSA Thanksgiving plans in 2013, we saw Silent Circle’s Blackphone roll out, Protonmail, with servers based in Switzerland, addressed the problem of email un-encryption, and the list continues. Go on Amazon and search “encrypted” to see the plethora of consumer electronics that are responding to the inculcated sense of privacy invaded. The gift shop brings us all these "necessities" to one place, situating them in the context of a political dissident who needs privacy. Compared with the website that shows the history of surveillance, this gift shop with its spiced up aluminum foil hats, now with a fashionable bill so you can blend it at the game, is much more meaningful in the history people watching out about being watched. Yet the nefarious reality is that consumer goods occupy an important role in surveillance, and military technologies more generally. In a hypothetical situation in which the developer of the IR-blocking wallet is the same person at MIT who developed the IR-reading technology that the wallet aims to block, we see the game that the defense industry plays, even if the biographical data of the developers isn't accurate.

So many modern luxuries and worthless junk lying around, all of which makes our lives as easy as they are come from military developments. GPS. Telegraphs. Wristwatches. Computers. Camouflage. Fully-automatic machine guns. But what was once a trickle-down to consumer goods have now become a subsidy by consumer to trickle up. The amount of consumer electronic spending far surpasses the amount of the Defense budget that’s earmarked for development. A billion smartphones sell per year, a staggering ledger on how much these companies can poor in R&D. Soldiers in Iraq are using Apple devices for translation, rather than wading through years of bureaucracy for bespoke design. How about a supercomputer made of PlayStation 3? Financially, many of these technologies could not maintain the pace of development without a consumer-base of street versions of these military grade defense weapons. The flow of tools between consumer and soldier is troubling not only because it appears that civilians are subsidizing killing that we may not condone through the use of technologies wrapped in gadget that we deeply covet, but also because our gadgets are getting imbued with tools that don’t necessarily reflect our needs. In the world of software, this is called “bloatware,” the apps included on a device, apps you didn't ask for, don't use, and don't need. The facial recognition capabilities of the iPhone and iPad, as seen in the Hansel and Gretel has nothing to do with a smartphone. We have 4-digit encryption, we have 7-digit encryption. We have fingerprint recognition, now facial recognition? How about scrotal recognition? How about test my DNA to make sure it’s really me and whether the user is biologically predisposed to drop this fucking phone in the toilet. VPN, NFC, most accessibility features have little use to consumers but readily align with the State Department needs.

Perhaps the most relevant of techno-trash that shines light on this incestuous holiday at the Park Ave Armory are drones themselves. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, UAVs, those friendly consumer-grade gadgets that guys are using to make every crane shot in every indie movie, or fly around on the beach or park, are ramping up. They're reaching commercial grade, now able to carry and deliver goods. Meanwhile, UAS, unmanned Aerial Systems, like the Reaper, which were used by the military for first surveillance and now to drop bombs, are getting smaller. 2.8 million UAVs have been sold already, while more and more militaries around the world are buying UAS. LOCUST, Low-cost UAV Swarming Technology says it all: they're taking the consumer scaled UAVs and making them useful in the battlefield, a hybrid between UAV and UAS.

Peephole, 2017

Weaponry wouldn't be complete without defense. Police and hired defense contractors are putting UAVs to use in crowd surveillance. Then there's the weapon against UAVs: The Dronegun, used to scramble the communication between the UAV and controller. Developed by John M. Franklin and Dr. Brian P. Hearing at Johns Hopkins Air and Missile Defense Sector, the technology is framed as protection for politicians, the military and the rich and famous. Dronegun's technology reveals growing use of UAVs by insurgency, fringe consumers who may want to assassinate someone, and technologically-endowed perverts.

UAS are a testament for the casualization of conflict, both in terms of policy and mortalities. Termed as "targeted killings" by the U.S., the questionable exodus from traditional realm of warfare dodges into a civilian context. The Authorization for the Use of Military Force, passed after September 11, 2001, is a carte blanche to kill anyone really anywhere at basically anytime. 93,547 bombs have been dropped as of August 23, 2017. Hypothetically limited to al-Qaeda, the Taliban and their buddies, the open door is whoever these buddies turn out to be, become, emerge or evolve. ISIS. ISIL. And anyone who lives in the neighborhood, city, country, or region where they may be found, or thought to be. (Death by Drone, pp. 27) Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia. Let's not forget that killing civilians is a war crime.

Drone strikes have increased under Trump, which increased under Obama. Civilian casualties have also increased. And it's not just the U.S. Saudi Arabia continues drone strikes on Yemeni rebels, as unmanned hunt and kill missions increasingly become the lingua franca of absentee diplomacy. Blocked by an international Arms Trade Treaty, Saudi Arabia has turned to Chinese military technology to continue their campaign against the Houthis, while Iranian produced drones given the rebels fire to return to Saudi Arabia, ostensibly turning Yemen into the stage for testing international weapon capabilities, a role Spain played prior to World War II.

Drone strikes are more secretive than manned attacks, presumably because the threat of a depressed parent of an fallen American soldier is less likely. And because the domain of the War on Terror is not limited to national boundaries, the attack by drones doesn't require the usual Congressional approval that a military act of aggression requires. Drones are the casual way of killing. We can see that, like most military weaponry that is applied to the foreign domain, it's soon applied to the domestic market, often without the regulation of historical courts of war. Hollow-tipped bullets, introduced by the British during the colonial wars in India, were outlawed by the Hague due to their excessive brutality. They are still lawfully used by U.S. police against civilians. So while technology is now trickling from the consumer up to the military, weaponry continues to trickle back down.

Future Throw Pillow, 2017

Notes

Airwars.org

https://airwars.org/

"Civilian Drones," The Economist, July 8, 2017

http://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2017-06-08/civilian-drones

"China's Saudi Drone Factory Compensates for US Ban," Middle East Eye, March 29, 2017

http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/china-build-factory-saudi-arabia-fill-drone-shortage-1200657135

Death by Drone, Open Society Foundations, New York, NY, 2015

"GPS, Drones, Microwaves and Other Everyday Technologies Born on the Battlefield," Les Shu, Digital Trends, May 26, 2014

https://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/modern-civilian-tech-made-possible-wartime-research-development/

"Key Staff," Droneshield, August 23, 20217

https://www.droneshield.com/key-staff

"LOCUST: Autonomous, swarming UAVs fly into the future," David Smalley, Office of Naval Research,April 14, 2015

https://www.onr.navy.mil/Media-Center/Press-Releases/2015/LOCUST-low-cost-UAV-swarm-ONR.aspx

"The Military Consumer Complex," The Economist, December 10, 2009

http://www.economist.com/node/15065709

"Military Tech Versus Street Tech: Who's Got the Edge?" James Vlahos, Popular Science, August 15, 2004

http://www.popsci.com/scitech/article/2004-08/military-tech-versus-street-tech-whoacutes-got-edge

"The (Not-So) Peaceful Transition of Power: Trump's Drone Strikes Outpace Obama," Micah Zenko, Council on Foreign Affairs, March 2, 2017

https://www.cfr.org/blog/not-so-peaceful-transition-power-trumps-drone-strikes-outpace-obama

"US Air Force Connects 1,760 PlayStation 3's to Build Supercomputer," Lisa Zyga, Physics, December 2, 2010

https://phys.org/news/2010-12-air-playstation-3s-supercomputer.html